Every second of every day, someone is typing in Chinese. In a park in Hong Kong, at a table in Taiwan, in the checkout line at a Family Mart in Shanghai, with the automatic doors playing a melody as they open. While the mechanics are somewhat different from typing in English or French—people typically type the pronunciation of a character and then choose it from a selection that appears automatically—it’s hard to think of anything more mundane. The software that enables this operates below the conscious level of nearly all its users. In other words, it simply exists and is barely noticed.

What has been largely forgotten—and what most people outside Asia never knew in the first place—is that a large group of eccentrics and linguists, engineers and polymaths spent much of the 20th century struggling with how Chinese could be moved away from the ink brush to some other medium. This process is the subject of two books published in the past two years: Thomas Mullaney’s The Chinese Computer, a more academic work, and Jing Tsu’s Kingdom of Characters, a more accessible book for the general public. Mullaney’s book focuses on the invention of various input systems for Chinese since the 1940s, while Tsu’s covers more than a century of efforts to standardize the language and transmit it via the telegraph, the typewriter and the computer. But both reveal a tumultuous and chaotic history—and a little unsettling for the sense of futility it reflects.

The problem, however, is that there are so many characters. To be considered basically literate, one must know at least a few thousand, and there are thousands more beyond that basic set. Many modern students of Chinese devote themselves almost full-time to learning to read, at least at first. More than a century ago, this task was so monumental that influential thinkers worried that it was undermining China’s ability to withstand pressure from more aggressive powers.

In the 19th century, a large portion of the Chinese population was illiterate. There was little access to formal education. Many were subsistence farmers. Despite its huge population and vast territory, China often found itself at a disadvantage in negotiations with more agile, industrialized nations. The Opium Wars of the mid-19th century resulted in a situation in which foreign powers effectively colonized Chinese soil. What advanced infrastructure existed had been built and controlled by foreigners.

Some believed that these problems were interconnected. Wang Zhao, for example, was a reformer who argued that a simpler way of writing spoken Chinese was essential to the nation’s survival. His idea was to use a set of phonetic symbols representing a specific dialect of Chinese. If people could pronounce words by memorizing just a few symbols—as speakers of alphabet-based languages do—they could become literate more quickly. With literacy, they could learn technical skills, study science, and help China regain control of its own future.

Wang believed so strongly in this goal that, despite being expelled from China in 1898, he returned two years later in disguise. After arriving by boat from Japan, he traveled overland on foot, dressed as a Buddhist monk. His story forms the first chapter of Jing Tsu’s book and is filled with dramatic scenes, including a heated argument and even a fight on the grounds of an old palace during a meeting to decide which dialect should represent the national version of this system. Wang’s method of learning Mandarin was adopted by schools in Beijing for a few years, but was eventually supplanted by the rise of competing systems and the period of chaos that engulfed China following the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911. Decades of disorder and uneasy truces culminated in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in northern China in 1931. For a long time, basic survival was the only concern for most people.

But curious inventions were also beginning to emerge in China. Chinese students and scientists abroad had begun working on a typewriter for the language, which they believed was falling behind others. Texts in English and other languages that used Roman characters could be printed quickly and cheaply with keyboard-controlled machines that injected liquid metal into typefaces. But Chinese texts required the manual placement of thousands upon thousands of small type blocks on a printing press. While English correspondence could be typed quickly on a typewriter, Chinese correspondence was still, even after all this time, written by hand.

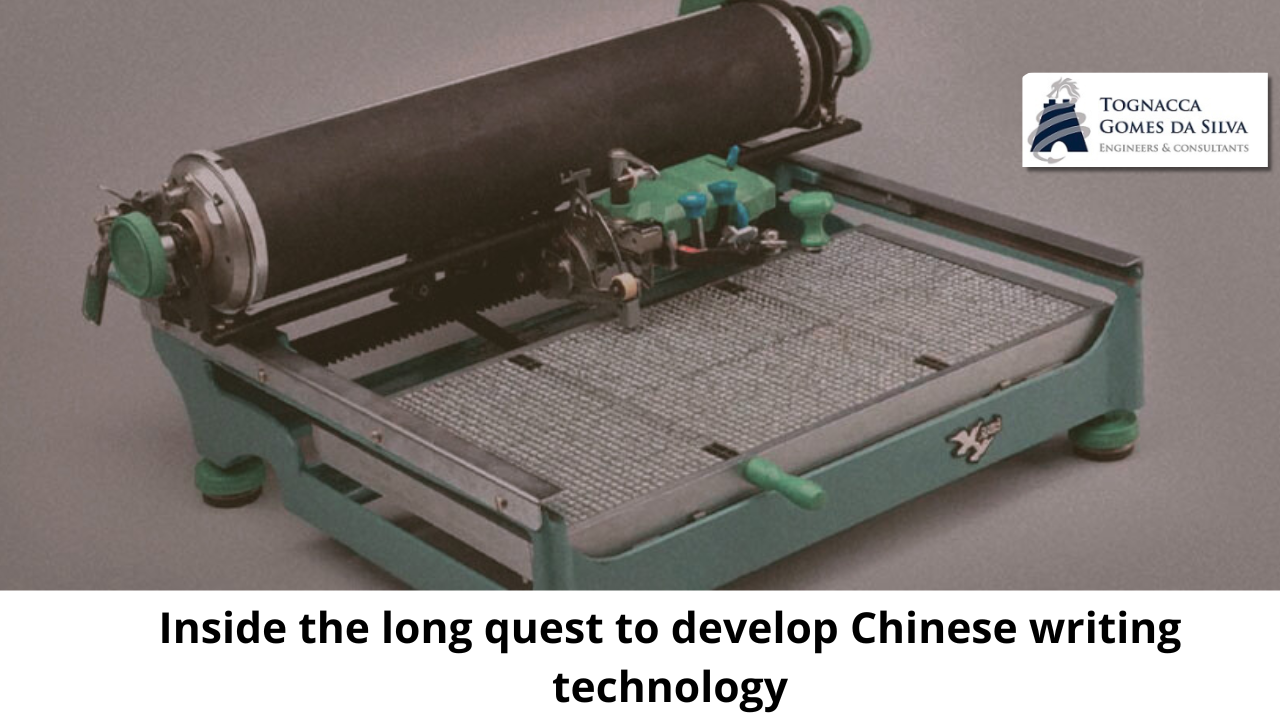

Of all the technologies described by Mullaney and Tsu, these complex metal machines are the most memorable. Equipped with cylinders and wheels, with type arranged in a star pattern or on a massive tray, they were both writing machines and embodiments of different philosophies about how to organize a language. Because Chinese characters have no inherent order (there is no equivalent to A-B-C-D-E-F-G) and there are so many of them (if you glance at 4,000 of them, you’re unlikely to find the one you need right away), the inventors tried to organize type according to predictable rules. The first paper published by Lin Yutang—who would later become one of the most renowned Chinese writers in English—described a system for ordering characters based on the number of strokes needed to write them. He ended up designing a Chinese typewriter that consumed his life and his finances—a beautiful piece of work that failed to demonstrate to potential investors.

Technology often demands new forms of physical interaction, and the Chinese typewriter was no exception. When I first saw a working one in a private museum in the basement of a building in Switzerland, I was fascinated by the delicate sliding arm and rails of the cake-sized device and its tray filled with characters. “Operating the machine was a full-body exercise,” Tsu writes of one of the first Chinese typewriters, designed in the late 1890s by an American missionary. Its inventor hoped that over time, muscle memory would take over, allowing the operator to move smoothly around the machine, selecting characters and pressing keys.

But while Chinese typewriters eventually caught on (the first commercial machine became available in the 1920s), a few decades later it became clear that the next challenge was to bring Chinese characters into the computer age. And then there was the problem of how to get more people to learn to read. During the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, systems for organizing and typing Chinese characters continued to occupy the minds of intellectuals. One particularly curious and memorable case is that of the librarian at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, who in the 1930s devised a system of light and dark glyphs, similar to traffic light flags, to represent characters.

In parallel, Mullaney and Tsu also delve into the story of Zhi Bingyi, an engineer who was imprisoned in solitary confinement during the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s. Inspired by the characters of a slogan written on the wall of his cell, he devised his own code to input characters into a computer.

As the daughter of a futurist, I saw firsthand that the path to today’s scientific heights is littered with technological dead ends.

Literacy tools were also advancing during this period, thanks to government reforms following the 1949 Communist Revolution. To help people learn to read, all citizens of mainland China were taught pinyin, a system that uses letters from the Roman alphabet to indicate the pronunciation of Chinese characters. At the same time, thousands of characters were replaced with simplified versions, with fewer strokes to memorize. This is still the method used in mainland China today, although in Taiwan and Hong Kong the characters were not simplified, and Taiwan uses a different pronunciation guide based on 37 phonetic symbols and five tone marks.

There were numerous attempts to introduce Chinese characters into computers. Mullaney’s book presents, with a melancholy touch, images of a graveyard of failed projects—keyboards with 256 keys and the enormous cylinder of the Ideo-Matic Encoder, a keyboard with more than 4,000 options.

In Tsu’s telling, perhaps the most significant link between this period of specialized hardware and today’s lightning-fast typing on mobile phones came in 1988, with an idea conceived by engineers in California. “Unicode was conceived as a universal converter,” she writes. “It would unify all human writing systems—Western, Chinese, or any other—under a single standard and assign each character a unique, standardized code for communication with any machine.” Once Chinese characters had Unicode codes, they could be manipulated by software in the same way as any other glyph, letter, or symbol. Today’s input systems allow users to call up and select characters using pinyin, stroke order, or other options.

Yet there is something curiously frustrating about the way both books end. Mullaney’s meticulous documentation of last century’s typewriters and Tsu’s collection of adventurous stories about the language reveal the same reality: An incredible amount of time, energy, and intelligence went into making Chinese characters easier for machines and human brains to manipulate. But few of these systems appear to have had a direct impact on current solutions, such as the pronunciation-based input methods used by more than a billion people today to type in Chinese.

This pattern of evolution is not unique to language. I have personally seen firsthand how the path to the present is littered with innovations that never quite caught on. The month after the launch of Google Glass, the smart glasses that had captured the media’s attention, my mother helped set up an exhibit of personal displays. In a dim warehouse space, white foam heads seemed haunted by crowns of metal, glass, and plastic—different inventors’ attempts to put a screen in front of our eyes. Augmented reality seemed to finally be making its way into people’s hands—or, more accurately, onto their faces. That version of the future has not come to fruition, and if augmented reality viewing ever becomes part of everyday life, it will not be through these devices. When historians write about these technologies, in books like these, I don’t think they will be able to trace a continuous line of thought, a single arc from idea to realization.

A charming moment toward the end of Mullaney’s book illustrates this point. He has been sending letters to people listed as inventors of input methods in the Chinese patent database, and now he is meeting one of those inventors—an elderly man and his granddaughter—at a Beijing Starbucks. The man excitedly talks about his approach, which is based on the graphic shapes of Chinese characters. But his granddaughter springs a surprise on Mullaney when she leans over and whispers, “I think my input system is a little easier to use.” It turns out that both she and her father have developed their own systems.

In other words, the story is not over yet.

People tinker with technology and systems of thought like the ones described in these two books not just because they have to, but because they want to. While it’s human nature to try to see a clear trajectory in the past, making the present seem like a grand culmination, what these books show are merely episodes in the life of a language. There is no beginning, no middle, and no satisfying end. There is only evolution—a continual unfolding of something that is always in the process of becoming a more complete version of itself.

Veronique Greenwood is a science writer and essayist based in England. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, The Atlantic, and many other publications.

( fontes: MIT Technology Review )