In 2004, Michel Gondry’s film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind captured the public’s imagination by exploring a provocative premise: what if it were possible to erase painful memories? Starring Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet, the film raised emotional and ethical questions about identity and the role of memories in our lives. What few realized at the time, however, was that science was beginning to follow a path that was surprisingly close to that of fiction.

Early developments

In the 1960s, psychologist Ulric Neisser, known as the father of cognitive psychology, began to suggest that the brain uses sleep to “organize” and consolidate memories. During sleep, the brain would have the ability to “filter” information, reinforcing important memories and discarding irrelevant information. This theory was one of the first to propose that sleep was an active process related to learning and memory.

In 1983, renowned scientist and Nobel Prize winner Francis Crick, who discovered the helical structure of DNA, delved into the topic of sleep and went deeper, suggesting that rest could not only be a storage filter, but also a modulator of memories.

In light of this, it is possible to say that sleep is more intelligent than we imagine. Much more than a rest break, it plays a crucial role in the consolidation of memories and emotional regulation. However, what if sleep could do more? What if, deep within, it hides the secret to erasing painful memories or rewriting past traumas?

Sleep and memory

Matthew Walker is a renowned British neuroscientist and researcher, known for his work on sleep and its impacts on human health and performance. He is the author of the best-selling book Why We Sleep: The New Science of Sleep and Dreams.

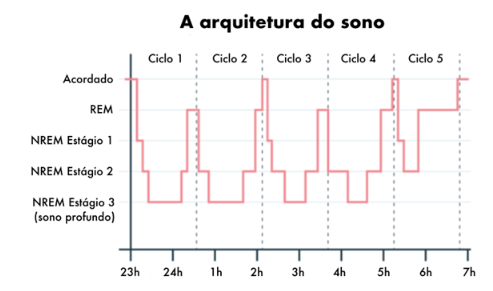

In the book, Walker explains the function of the different stages of sleep, as shown in the figure below. The best-known part of our sleep is REM (Rapid Eye Movement), a time when our eyes move quickly from one side to the other. This phase occurs at the end of sleep and is responsible for dreams and the unconscious processing of problems that we need to solve. During the rest of our sleep, which corresponds to almost 6 hours of the total 8, we are in NREM (non-REM) mode, that is, deep sleep. Although most of the research attention is on REM, Walker and his team discovered that the NREM cycle is more important than we imagine, and is responsible for storing memories.

This means taking short-term memories (hippocampus), evaluating them, and selecting them. Finally, this cycle filters out memories that will be stored for the long term (the cortex).

Figure from the book “Why We Sleep”

Although the concept of “erasing” erroneous memories is an oversimplification, recent studies suggest that sleep—especially NREM sleep—plays an important role in regulating and refining memories, as well as in learning and decision-making.

Walker’s experience

In 2009, Walker conducted the following experiment: individuals were exposed to a sequence of random words on a computer, some of which were marked with the letter R (Retain) to remember and others with the letter F (Forget) to forget. The idea was to test whether the brain would be subject to storage commands.

The participants were divided into two groups: one that took a nap (the Nap group) and the other that remained awake (the No-Nap group). During the learning phase, they were given words accompanied by instructions to remember (R) or forget (F) each one. After a sleep interval or without sleep, the participants performed a free recall test. The results showed that sleep selectively increased the recall of the words marked for recall, without facilitating the recall of the words designated for forgetting.

After watching the images, the group was divided into two. The first group was to stay awake and the second group was allowed to sleep for 90 minutes. After a few hours, a memory test was performed that showed the ability of sleep to increase the ability to memorize words marked with the letter R, disregarding the recall of words marked to be forgotten. In other words: the brain responded to commands during the sleep filter.

Association with sound

In 2009, Ken Paller and his team conducted a study on memory reactivation during sleep, known as Targeted Memory Reactivation. In the experiment, participants were trained to associate 50 images of unique objects with specific locations on a computer screen. Each image was paired with a characteristic sound—such as “cat” with “meow” or “kettle” with “whistle”—which helped reinforce the connection between the object and its corresponding location.

During the participants’ sleep, the sounds of half of the objects (25 in total) were repeatedly presented to reinforce the memory of these associations. After waking, the participants were asked to view all 50 images again and try to position them in their original locations. The results showed that in 10 of the 12 participants, the placements of the objects were more accurate for those who had been stimulated by their sounds during sleep. This suggests that memory reactivation through sensory stimuli during sleep may play an important role in selective memory consolidation.

Negative images

Recently, scientists at the University of Hong Kong applied the TMR technique to investigate the possibility of attenuating the impact of negative memories, extending the concept of the influence of sound on memory consolidation.

In the experiment, 37 volunteers in their 20s were exposed to 48 negative images, each associated with recorded sound words. During sleep, the negative images were stored in the brain along with the corresponding sounds.

The next day, the participants viewed positive images and tried to associate some of the recorded sound words with the new images. Some positive images were associated with the same sounds as the previous negative images.

On the second night, the sounds were played while the participants slept. Questionnaires conducted after the experiment revealed that the participants had more difficulty remembering the negative images that were “overwritten” by the positive images, suggesting that the TMR technique could help reduce the impact of negative memories.

Traumas and old memories

Although promising, the results obtained in TMR studies were all conducted in laboratory settings, which presents some limitations for the application of the technique in real life. One of the main difficulties is that traumas usually do not have sounds, which makes the direct application of TMR impossible.

However, new research may explore alternative approaches (such as regression techniques or hypnosis) to access and retrieve these memories and, in this way, associate them with specific sounds in the present.

Ethical issue

Erasing memories can have a series of complex consequences on the individual’s neural network, which raises concerns about the impacts of this practice. Many prefer, therefore, to use the term “memory reconsolidation”: this process – in theory more controlled – “reprioritizes” or “resensitizes” memories, seeking to reduce their negative effects, but without eliminating the memory itself.

Even so, this type of approach would only be permitted in cases with a confirmed clinical indication, ensuring that only people with specific conditions and after a careful evaluation would be treated.

Although they demonstrate potential, the studies carried out to date are still limited to laboratory settings. It is crucial, however, that this technology be used with caution to avoid abuse. In this context, the potential to alter memories beyond trauma, for ideological or political purposes, raises ethical and moral questions that cannot be ignored. Any advances in this field must be accompanied by strict regulations to ensure that memory interventions are only performed when clinically indicated and with the informed consent of the individuals.

( fontes: MIT Technology Review)